Addressing LGBTQ Student Bullying: Student and School Health Professional Perspectives

/in Blog/by adminComparing Barriers to HIV Care in DE: Client and Provider Perspectives

/in Homepage News, Blog/by adminMaternal Experiences with Everyday Discrimination and Infant Birth Weight: A Test of Mediators and Moderators Among Young, Urban Women of Color

/in Homepage News, Blog, Uncategorized/by Valerie EarnshawBy Jamie Scharoff

What do we already know?

There are pronounced racial and ethnic differences in birth weight among newborns in the United States. In 2009, the rate of low birth weight was 5.23% for White women, 5.72% for Latina women, and 11.44% for Black women. Low birth is associated with health problems among infants, and is one of the three leading causes of infant death. In adulthood, low birth weight is associated with diminished lung function and cardiovascular disease. Evidence suggests that being exposed to different types of discrimination can be related to poor health. Taking this one step further, these experiences of discrimination are linked to reports of depressive symptoms. When experienced by pregnant women, depressive symptoms can impact their infants’ birth weight.

What do we want to know?

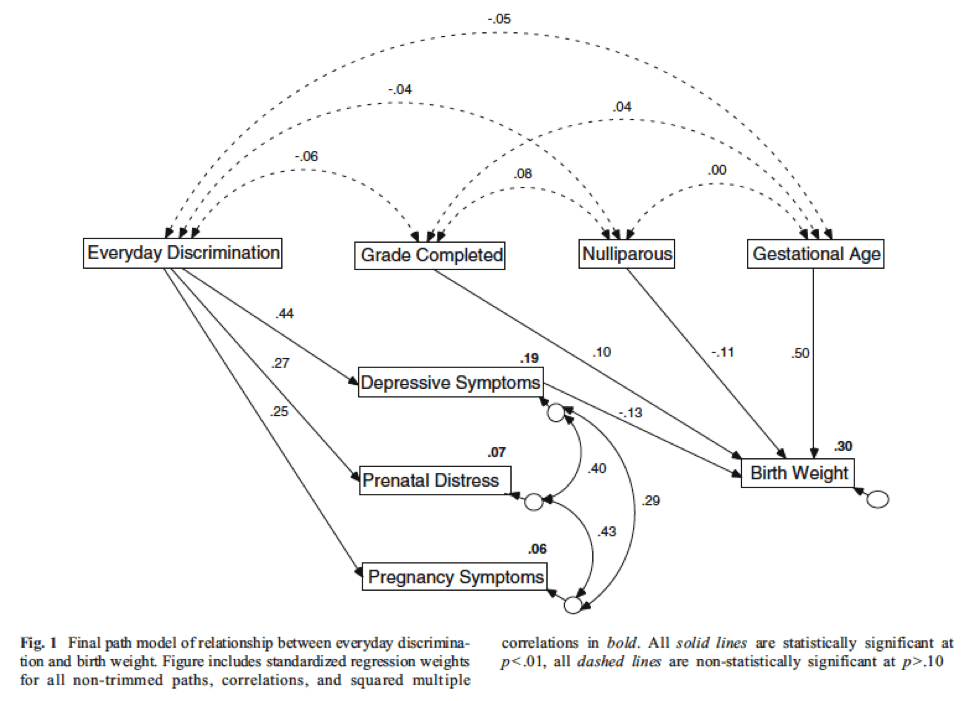

Most past research on discrimination and disparities in birth outcomes had focused on African American women specifically. Earnshaw and colleagues wanted to investigate these associations among urban Latina and Black pregnant young women (aged 14-21). The purpose of the study was to examine the link between maternal discrimination and infant birth weight among young urban women of color. Mediators are variables that can explain why discrimination may be associated with birth weight. In this study, the researchers explored the mediators of depressive symptoms, pregnancy distress, and pregnancy symptoms, all variables that if experienced by the mother during pregnancy have the potential to cause increased likeliness of giving birth to a baby with a low birth weight. Moderators are variables that have the potential to affect the strength of the association between mothers’ experiences and the infants’ low birth weight. The moderators in this study were age and race/ethnicity, because they wanted to see if younger women for example were more vulnerable to the effects of discrimination than older women.

What did they do?

The researchers recruited pregnant young women aged 14-21, who were referred by health care providers between 2008 and 2011. Baseline interviews were conducted during their second trimester of pregnancy, second interviews were conducted during their third trimester, and final interviews were conducted 6 and then 12 months postpartum. During the participant interviews, everyday discrimination, depressive symptoms, pregnancy symptoms and pregnancy distress were measured. Information about the infants, including birth weight, was recorded from the infants’ birth records. 420 women were included in these analyses.

What did they find?

The researchers found that everyday discrimination experienced by pregnant women was associated with lower birth weight among their infants. In addition, measures of depressive symptoms were found to serve as a mediator to the relationship between lower birth weight and everyday discrimination. This means that when women who experienced everyday discrimination during their second trimester reported more depressive symptoms later on in their third trimester. In turn, women with more depressive symptoms had babies with lower birth weights. Women who experienced more discrimination reported more pregnancy distress and symptoms, but pregnancy distress and symptoms were not associated with infant birth weight.

Another important finding was that none of the moderators affected this relationship. Therefore, maternal everyday discrimination affected infant birth weight no matter the woman’s age or race/ethnicity. Although a relationship between everyday discrimination and birth weight was uncovered, on average participants reported experiencing everyday discrimination infrequently.

So what?

This research shows that exposure to everyday discrimination is impacting young urban women of color and their babies. These experiences of everyday discrimination coupled with depressive symptoms may lead to disparities in their children’s birth weights. When these children are born with low birth weight it puts them at risk for life-long health complications such as infant death, chronic lung disease and even cardiovascular disease in adulthood. Experiences of everyday discrimination and depressive symptoms in young urban women of color need to be addressed. Treating these depressive symptoms could help to lessen the impact that discrimination has on their children’s birth weight. Finding ways to eliminate discrimination so that no women experience it is also critically important.

Reference: Earnshaw, V.A., Rosenthal, L., Lewis, J.B., Stasko, E.C., Tobin, J.N., Lewis, T.T., Reid, A.E., & Ickovics, J.R. (2013). Maternal experiences with everyday discrimination and infant birth weight: a test of mediators and moderators among young, urban women of color. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 45(1), 13-23.

Discrimination and Sexual Risk Among Young Urban Pregnant Women of Color

/in Homepage News, Blog/by Lia ValenzuelaDiscrimination and Excessive Weight Gain During Pregnancy Among Black and Latina Young Women

/in Homepage News, Blog/by Valerie EarnshawBy Cayla Scheintaub

Fatigue. Nausea. Headaches. Dizziness. These are just some of the burdensome physical symptoms that women experience during pregnancy. Some women also experience burdensome social interactions during pregnancy due to their race, ethnicity and/or age. This discrimination may lead to excessive weight gain and possible obesity of one’s child later on in life.

What do we know?

A great number of women gain weight beyond medical recommendations during pregnancy. Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is a determinant of obesity later on in life. Experiencing discrimination on a regular basis is related to an increase in waist size and abdominal fat over time and ultimately, leads to increased weight. Socio-demographic factors including race, ethnicity and age all pose a risk to excessive weight gain during pregnancy. Additionally, depressive symptoms may have an impact on excessive weight gain.

Who does this study concern?

In this study, there were a total of 413 young Black and Latina women; some were both Black and Latina. Data were collected from fourteen study sites in New York City. At these sites, the women received prenatal care. The study required that women be 14 to 21 years old, no more than 24 weeks pregnant, not a high-risk pregnancy and able to use English or Spanish.

What was found?

- Having ever experienced discrimination was linked with a 71% increased odds in excessive weight gain during pregnancy

- When the women had low depressive symptoms, discrimination predicted excessive weight gain. When women had high depressive symptoms, discrimination had NO association with excessive weight gain.

Overall, results demonstrate the role of discrimination in weight-related health inequalities and suggest opportunities for improving health outcomes among young pregnant women

What can we do in the future?

It is important that women receive regular, non-discriminatory healthcare during pregnancy to monitor for weight gain. Interventions should be developed to prevent the impact of discrimination on pregnant women, and to eliminate discrimination toward pregnant women. Discrimination and obesity are both problems in the U.S. and it is important to take precautionary measures against them.

Reference: Reid, A. E., Rosenthal, L., Earnshaw, V. A., Lewis, T. T., Lewis, J. B., Stasko, E. C., Tobin, J. N., & Ickovics, J. R. (2016) Discrimination and excessive weight gain during pregnancy among Black and Latina women. Social Science & Medicine, 156, 134-141. PMC4847945

Medical mistrust in the context of Ebola: Implications for intended care-seeking and quarantine policy support in the United States

/in Homepage News, Blog/by Valerie EarnshawBy Katie Tarantowicz

“America in the end is not defined by fear. We don’t just react on our fears. We react based on facts and judgment and making smart decisions” President Obama, 2014

The Ebola outbreak of 2014 came with a great deal of stigma. For example, several asymptomatic physicians who were treating Ebola in West Africa underwent unnecessary quarantine procedures when they returned to the United States. At the time, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention only stated that these people should be monitored for a certain period of time with no quarantine at all.

Public reactions to infectious diseases may have to do with medical mistrust, which involves a suspicion of and lack of confidence in medical organizations and providers. This can be a significant problem when patients feel they cannot rely on physicians or hospitals and so don’t seek treatment from them.

Medical mistrust can manifest in the form of conspiracy beliefs, which are beliefs that medical organizations and providers are plotting to harm people. Valerie Earnshaw, Laura Bogart, Michael Klompas, and Ingrid Katz were interested in learning about the effects that conspiracy beliefs can have on health behaviors in the context of an infectious disease outbreak like Ebola.

How did they get their data?

The data were collected using an online survey. The participants were 202 people from the United States over the age of 18. They measured agreement with conspiracy beliefs with four items including “There is a cure for Ebola, but it is being withheld”.

In order to measure each participant’s intended care seeking, the survey also asked what they would do if they had Ebola when given four options (such as “go to the hospital”). They were then asked to rate these options from what they were most to least likely to do.

Additionally, they were asked about their opinions on quarantine policies, medical mistrust in general, and xenophobia (prejudice towards foreigners). Questions on their levels of knowledge and fear of Ebola were also included.

How was it analyzed?

The sample was divided into participants who rejected conspiracy beliefs and those who neither rejected nor agreed with them, from the people who agreed with conspiracy beliefs. They looked at how their responses to conspiracy belief questions were associated with participants’ intended care seeking and their thoughts on quarantine.

What did they find?

16% of participants agreed with the Ebola conspiracy beliefs. On average, participants said that they were likely to engage in care-seeking and supported quarantines.

Participants who agreed with conspiracy beliefs reported:

| Lower levels of: | Higher levels of: |

| · Ebola knowledge

· Intended care-seeking · Support for quarantining people who have had contact with Ebola patients |

· Medical mistrust

· Xenophobia |

So what does this mean?

These results are similar to national rates of agreement with other kinds of conspiracy beliefs, such as the belief that there was a deliberate infection of Black Americans with HIV (12% of U.S. adults agree with this) and the belief that vaccines can affect autism (20% agree).

Because participants who believed conspiracy theories would be less likely to seek care, this form of mistrust of medical professionals could negatively impact a person’s health during a disease outbreak.

People who were believed in conspiracies were not likely to support quarantine. This could be because most conspiracy theories are based off of powerful figures imposing strict regulations on people, which is exactly what was happening in the context of strict quarantine procedures during the Ebola outbreak. People who believe conspiracies may distrust quarantines.

Conclusion

President Obama very wisely pointed out in a speech on the Ebola outbreak that Americans should not define their beliefs based off of fear, but instead based off of facts and judgement. These findings suggest that some US citizens actually may have reacted to this outbreak based on fear, mistrust, and conspiracy beliefs rather than facts and judgment. If we could aspire to learn the facts and make informed judgements rather than letting our fear take over, stigma surrounding infectious diseases such as Ebola could be greatly reduced.

Reference: Earnshaw, V. A., Bogart, L. M., Klompas, M., & Katz, I. T. (in press). Medical mistrust in the context of Ebola: Implications for intended care-seeking and quarantine policy support in the U.S. Journal of Health Psychology.